Introduction: what “long‑term hold” means and why it’s rising

Traditional private equity (PE) funds operate on a buy‑improve‑sell model: acquire a business, implement operational initiatives and divest within three to five years. This structure creates multiple transactions over a decade and forces exits based on fund life rather than business performance. In the lower‑middle market (LMM), however, a different model is gaining traction. Long‑term hold, often called permanent capital or long‑term private capital (LTPC), refers to ownership with horizons of seven to ten years or longer. Instead of raising successive finite‑life funds, investors raise evergreen or long‑dated vehicles and own assets until the timing is optimal.

The shift is visible in data: the median holding period for U.S. PE‑backed companies reached 3.4 years in 2024, the longest in nearly a decade; more than 30 % of companies were held for at least five years. Facing a weak exit environment, buyout funds are using continuation vehicles to roll high‑quality assets into new structures; continuation fund numbers have quadrupled over five years and accounted for 84 % of GP‑led secondary volume in 2024. Investors such as family offices, pension plans and operator‑led groups are raising evergreen holding companies that resemble Berkshire Hathaway, Constellation Software and Roper Technologies. The core thesis: holding businesses longer unlocks tax‑efficient compounding, deeper operational value creation and the ability to exit when markets are favorable.

1 Economic logic: compounding, timing optionality and fewer frictions

Compounding gains by reducing churn

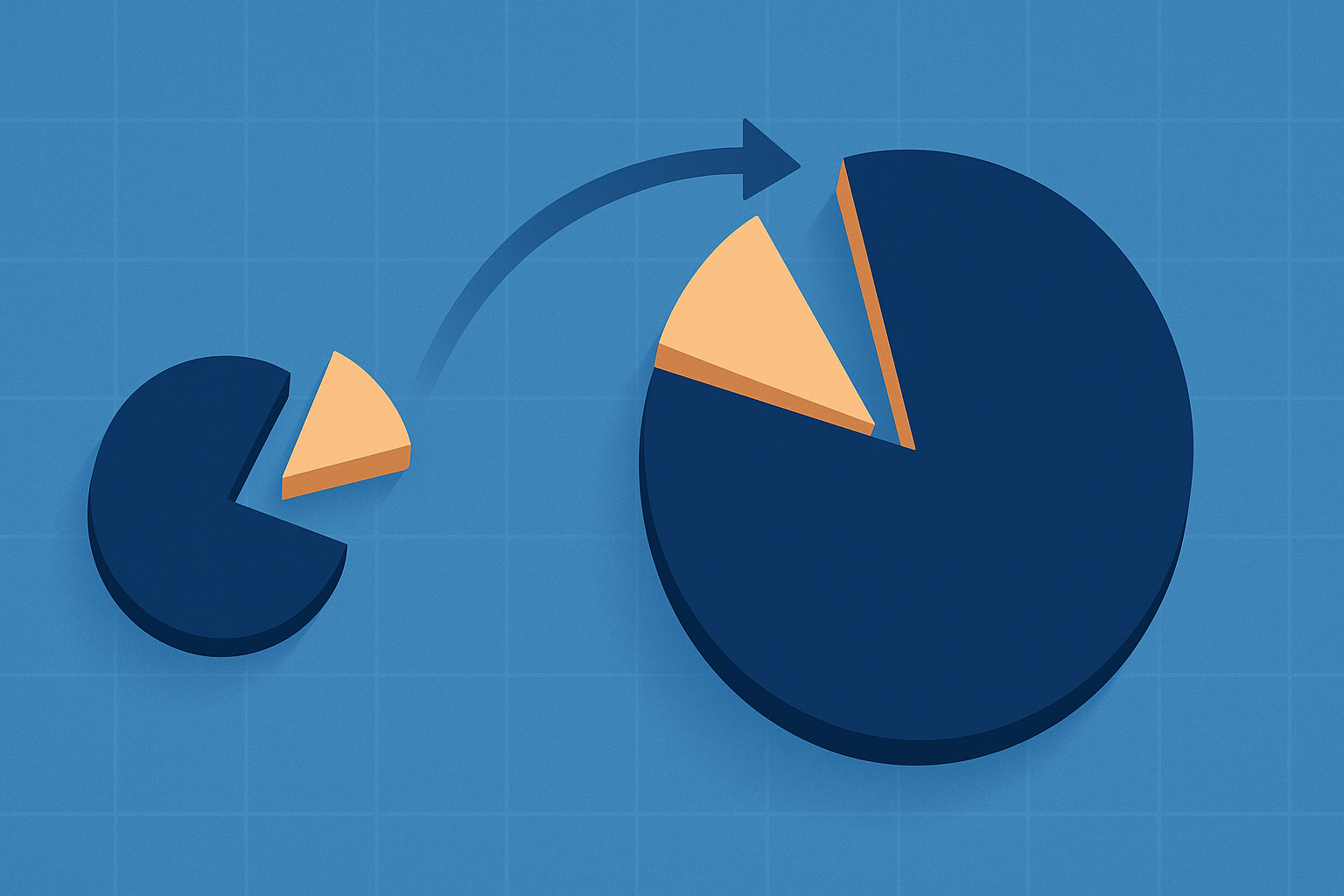

Each time a company is sold, transaction fees, taxes and frictional costs erode returns and capital leaves the compounding engine. A Bain analysis compares a long‑hold fund that keeps a company for 24 years with a traditional fund that sells the same asset four times. By eliminating repeat transaction fees, deferring capital‑gains taxes and keeping capital fully invested, the long‑hold model nearly doubles after‑tax returns. IFM Investors’ modelling of a similar scenario found that a long‑hold fund outperformed the short‑duration fund by almost two times after taxes and fees. These results illustrate how compounding pre‑tax cash flows over decades creates more wealth than recycling capital every few years.

Timing optionality and avoiding forced exits

Traditional funds must harvest companies when the fund is nearing its end. In 2024, exit value in U.S. PE fell to $277 billion, the lowest in over a decade. Some vintages realized only 20 % of their portfolio value, leaving investors with large unsold holdings. Long‑term holders are not forced to sell in down markets; they can ride out industry cycles and harvest when valuations are stronger. Longer horizons also allow owners to integrate tuck‑in acquisitions gradually, implement pricing initiatives and optimize working capital without the distraction of an impending sale.

Fewer transaction frictions and lower fee leakage

Short‑duration funds frequently sell companies to other PE buyers. In 2015 research, about 40 % of private equity exits were secondary buyouts, meaning assets cycled among funds. Every handoff incurs new diligence costs, financing fees, carried interest and potential tax events. For limited partners, redeploying capital also consumes time and resources. Long‑term capital alleviates redeployment issues and captures the compounding effect of reduced transaction fee leakage.

2 Tax efficiency and after‑tax returns

Deferral of realization and the lock‑in effect

U.S. capital‑gains tax is assessed at realization; investors can defer the tax by holding assets longer, creating a “lock‑in effect”. Economic research notes that realization‑based taxation encourages long holding periods because gains are compounded pre‑tax. Long‑term investors therefore benefit from compounding on capital that would otherwise be paid in taxes.

Long‑term vs. short‑term capital gains and carried interest rules

Under current U.S. law, gains on assets held more than one year are taxed at long‑term capital‑gains rates. Section 1061 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) recharacterizes certain gains from applicable partnership interests (carried interest) as short‑term if the holding period is less than three years. Long‑term holds therefore reduce the risk that carry recipients are taxed at ordinary‑income rates.

Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS/§ 1202)

Section 1202 allows non‑corporate taxpayers to exclude up to 100 % of the gain from the sale of qualified small‑business stock (QSBS) if the stock is held for more than five years and other requirements are satisfied. The exclusion is limited to the greater of $10 million or 10 × the stock’s basis. While many lower‑middle‑market companies are limited liability companies (LLCs) or S‑corps and may not qualify, planning early around entity structure can preserve this potential benefit.

Installment sales, continuation vehicles and deferral

Continuation vehicles enable sponsors to roll high‑quality companies into new vehicles funded by secondary investors, providing liquidity to existing limited partners without triggering a full sale. Such GP‑led secondaries grew to a record $63 billion in 2024. Installment‑sale structures or earn‑outs can also spread recognition of gain over several years. Owners contemplating these strategies should coordinate with tax advisors.

Estate planning and step‑up in basis

Upon death, inherited assets receive a step‑up in basis to fair market value, eliminating capital gains on appreciation during the decedent’s life. Long‑term holds can therefore be integrated into estate plans to pass businesses to heirs with a higher basis. However, proposals to limit step‑up treatment remain under debate.

Disclaimer: The preceding discussion is general information, not tax advice. Tax consequences vary by jurisdiction, entity type and individual circumstances; readers should consult qualified advisors.

3 “Value left on the table” when exiting right after the build‑out

Search‑fund and LMM data reveal that exiting shortly after professionalizing a business often transfers the upside to the next owner. The international search fund study reports that deals generating more than 10× returns were held for an average of 10.4 years, while those yielding 5–10× returns were held about 5–6 years. By contrast, investors who exited after three to four years typically achieved lower multiples. Stanford’s 2024 research shows that search‑fund exits between 2018 and 2021 had a mean holding period of 5.9 years, whereas the average dropped to 4.8 years for 2022–2023 exits. Many entrepreneurs rolled equity into new deals and continued as CEO, reflecting the belief that operating leverage and growth materialize after the early build‑out.

Professionalizing a business—installing a robust ERP/CRM, recruiting senior leaders and creating scalable pricing models—typically takes 18–24 months. Bain’s analysis of 33 software buyouts found that 94 % expected margin improvement of about 560 basis points over five years, yet actual margins lagged after five years. The biggest gains often accrue after the initial systems and culture work, through cross‑selling, pricing optimization and customer‑success programs that compound over subsequent cycles. Selling immediately after professionalization hands these benefits to the next owner.

4 Operating advantages of longer holds

-

Talent flywheel: Recruiting A‑players and aligning incentives around a multi‑year scorecard fosters loyalty and reduces the churn that accompanies frequent ownership changes. Long‑term owners can design equity plans that vest over five to ten years and tie bonuses to cumulative value creation.

-

Commercial excellence: Pricing and packaging programs, customer‑success initiatives and net‑revenue‑retention (NRR) metrics require multiple budgeting cycles to test and refine. Longer holds provide time to experiment with tiered pricing, attach rates and cross‑sell initiatives without being constrained by an imminent exit. Contract renewal cycles also align better with seven‑ to ten‑year ownership.

-

Systems and analytics: Implementing ERP, CRM and RevOps infrastructure is costly and disruptive. Returns on these investments show up in later years through improved cash conversion and data‑driven decision making. Long‑term investors can upgrade systems, train teams and realize the benefits of data analytics that might not materialize within a three‑year window.

-

Platform M&A: Lower‑middle‑market platforms often use patient, smaller tuck‑in acquisitions to build market share. Longer horizons allow integration to proceed deliberately—retaining acquired talent, harmonizing cultures and systems, and avoiding “deal heat.” The ability to integrate four or five tuck‑ins over ten years can transform a $10 million EBITDA business into a regional champion without overleveraging.

5 Berkshire, Buffett & Munger: playbook inspiration

Warren Buffett’s 1988 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders captured the essence of permanent capital: “When we own portions of outstanding businesses with outstanding managements, our favorite holding period is forever”. Berkshire avoids selling winners and focuses on quality businesses with durable moats, decentralized management and disciplined capital allocation. Several principles translate directly to LMM investing:

-

Invest in quality businesses with enduring competitive advantages—e.g., niche market leaders or businesses with high switching costs. Vertical‑market software platforms like Topicus and Constellation Software follow this model, acquiring vertical software vendors and allowing them to operate autonomously while reinvesting free cash flow for decades.

-

Decentralized autonomy with accountability: Berkshire delegates operational control to local management while setting capital‑allocation guardrails. This approach suits LMM companies, where founder/operators remain in place and know their markets.

-

Low turnover and tax‑efficient compounding: Frequent trading creates taxes and friction. Holding businesses for long periods allows compounding pre‑tax earnings and deferring capital gains.

-

Disciplined M&A: Berkshire, Roper, Danaher and HEICO acquire businesses that generate cash and have durable moats. Their track records show that long‑term integration and patient capital can produce strong risk‑adjusted returns without forced exits.

6 Evidence: holding periods, continuation vehicles and outcome dispersion

Hold periods across the PE industry are lengthening as market conditions and investor preferences shift. The median hold period reached 3.4 years in 2024, and more than 30 % of companies were held for over five years. Distributions as a percentage of net asset value (NAV) fell from 29 % in 2014–2017 to 11 % in 2024, signaling that investors are reinvesting rather than exiting. Continuation vehicles—a key long‑hold tool—grew to $601 billion in assets under management by 2024, with the number of vehicles quadrupling and total value nearly tripling over five years. Cambridge Associates’ 2025 outlook notes that continuation vehicles are likely to become an even more important exit path.

Secondaries sponsors underwrite continuation vehicles to 2–3× net multiple on invested capital (MOIC) with 20–25 % internal rates of return (IRR). This shows that long‑term hold strategies can generate competitive returns while providing liquidity options for existing investors.

Within the search‑fund universe, high‑return outcomes correlate with long hold periods: the 2024 international study reports that high‑return deals stay under owner‑operator stewardship for over a decade. This dispersion underscores the importance of patience.

7 Risks and when long‑term hold is the wrong fit

Long‑term ownership is not universally appropriate. Bain warns that distressed properties, turnaround candidates or cyclical plays may not perform well when held indefinitely. Investors must assess duration risk—technological shifts, regulatory changes and competitive threats—and re‑diligence portfolio companies every three to four years. If risks become too high, owners should “pull the rip cord and sell”. The IFM white paper notes agency risk: short‑term focus can drive inappropriate decisions that erode long‑term value. Long‑term capital also reduces liquidity; investors should be prepared for extended lock‑ups and the possibility that underperforming assets tie up capital for years.

Guardrails mitigate these risks:

-

Capital allocation discipline: Establish hurdle rates and scorecards for reinvestment vs. distribution. If returns on incremental projects fall below the hurdle, distribute excess cash or consider sale.

-

Periodic exit readiness: Even when not planning to sell, maintain updated data rooms, KPI time series and third‑party valuations. This ensures management is “exit‑ready” and forces a strategic review.

-

Board cadence and governance: Long‑term owners should refresh boards periodically, schedule deep dives into strategy and risk, and ensure accountability to avoid complacency. Company‑level audits every few years help reassess strategy in light of technology and regulatory changesbain.com.

-

Style discipline: Resist the temptation to allocate capital outside the original mandate or pursue flashy but misaligned acquisitions. This helps avoid style drift and protects investor trust.

8 Playbook: How owners & investor‑operators pivot to long‑term hold (6–12 months)

-

Capital‑allocation charter – Define reinvestment vs. distribution policies, hurdle rates and return thresholds. Use a rolling five‑year plan to match investments with available free cash flow and risk tolerance.

-

Governance & autonomy – Implement quarterly value‑creation reviews with decentralized operating teams. Empower local leaders to make decisions but hold them accountable to transparent KPIs.

-

Tax & structure – Evaluate entity type and potential eligibility for QSBS (§ 1202); plan for the § 1061 three‑year holding period for carried interest; understand continuation‑vehicle mechanics; model installment‑sale options; incorporate estate planning such as step‑up in basis. Coordinate with tax advisors.

-

Operating cadence – Develop a pricing roadmap, customer‑success leading indicators (net and gross revenue retention), cost‑to‑serve analysis and cash‑conversion cycle tracking. Use data from ERP/CRM systems to support decisions.

-

M&A & integration – Adopt a “slow is smooth” approach to tuck‑in acquisitions: conduct cultural and operational diligence, integrate systems methodically and retain key talent. Use long‑term capital to avoid overleveraging.

-

Exit optionality – Always be exit‑ready. Maintain a living data room, update valuations and monitor debt capacity. Consider continuation vehicles or partial liquidity events to balance investor liquidity needs with long‑term value creation.

Comparison: long‑term hold vs. traditional flip

| Dimension | Long‑term hold (≥7–10 yrs) | Traditional flip (≈3–5 yrs) |

|---|---|---|

| Tax drag over lifecycle | Realize gains later; opportunity for QSBS or step‑up basis | Gains realized multiple times; more capital‑gains tax events |

| Transaction costs | Fewer sales and financings reduce advisory fees and diligence costs | Frequent entry/exit fees erode returns |

| Compounding runway | Cash flows reinvested for decades; compounding pre‑tax earnings | Limited window to implement value creation; compounding interrupted |

| Cycle‑timing risk | Can wait out downturns and exit in strong markets | Fund‑life constraints force exits even during downturns |

| Talent retention | Multi‑year equity plans align employees with long horizons | Employees face uncertainty as new owners cycle in |

| Systems/analytics maturity | Enough time to implement ERP/CRM and realize benefits | Upgrades may not fully pay off before sale |

| Leverage recycling | Lower leverage levels; more conservative capital structure | Higher leverage to amplify returns; refinancing risk |

| Use of continuation vehicles | Common to provide liquidity and maintain control | Rare; assets sold outright to next buyer |

| Governance cadence | Long horizons require periodic re‑diligence and board refreshes | Fund life dictates governance; boards focus on near‑term exit |

Conclusion: the case for patience

The resurgence of long‑term hold strategies in the lower‑middle market reflects more than ideology. It is a pragmatic response to tighter exit markets, rising transaction costs and the desire to compound capital tax‑efficiently. Evidence from search funds, secondary markets and long‑hold modelling shows that patient capital can deliver superior after‑tax wealth. Operationally, long horizons allow investors and owner‑operators to build talent flywheels, mature systems, drive pricing excellence and integrate tuck‑in acquisitions without the pressure of a looming sale. However, long holds are not universally appropriate; investors must regularly re‑assess duration risk, guard against complacency and maintain exit readiness.

For owner‑operators and investor‑operators considering a pivot to long‑term hold, the immediate steps are clear:

-

Draft a capital‑allocation charter setting reinvestment thresholds and distribution policies.

-

Conduct a tax and structure review to evaluate potential eligibility for QSBS, assess the impact of § 1061 on carried interest and plan for estate considerations such as step‑up in basis.

-

Create a continuation‑path memo documenting scenarios in which a continuation vehicle or installment sale would be used to provide liquidity without losing control.

-

Build an exit‑ready KPI pack with updated financials, systems data and rolling valuations; refresh this pack quarterly to maintain optionality.

-

Implement a board and governance cadence that aligns with long‑term horizons—periodic re‑diligence, cultural health checks and strategy resets.

By embracing patience, aligning incentives and maintaining discipline, LMM owner‑operators can capture the upside that shorter‑term investors often leave on the table.

References

-

IFM Investors (2022). Private equity – buy and hold: the role of long-term private capital in your portfolio. IFM Investors. Available at: https://www.ifminvestors.com (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

PitchBook (2025). US PE Breakdown 1H 2025. PitchBook Data Inc. Available at: https://pitchbook.com (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

Monument Group (2025). Secondaries and Continuation Vehicles: 2025 Market Insights. Monument Group. Available at: https://www.monumentgroup.com (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

Topicus.com (2024). Q4 2024 Management Discussion & Analysis. Topicus.com. Available at: https://cdn.topicusplatform.nl (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

Bain & Company (2025). Global Private Equity Report 2025. Bain & Company. Available at: https://www.bain.com (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

Finhouse (2024). Private Equity Exit Environment: 2024 Update. Finhouse.be. Available at: https://www.finhouse.be (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

Econlib (2023). Capital Gains Taxes and the Lock-In Effect. Library of Economics and Liberty. Available at: https://www.econlib.org (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

National Bureau of Economic Research (2023). Capital Gains Taxation and Lock-In. NBER Working Paper No. 32951. Available at: https://www.nber.org (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

Internal Revenue Service (2025). IRC §1061 – Carried Interest. U.S. Department of the Treasury. Available at: https://www.irs.gov (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

Plante Moran (2024). Almost Too Good to Be True: The Section 1202 QSBS Exemption. Plante Moran. Available at: https://www.plantemoran.com (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

WilmerHale (2024). Qualified Small Business Stock under IRC §1202. WilmerHale. Available at: https://www.wilmerhale.com (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

University of Nebraska–Lincoln (2024). Step-Up in Basis at Death: Estate Planning Considerations. Center for Agricultural Profitability. Available at: https://cap.unl.edu (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

One to One Funds (2024). International Search Funds 2024 Report. IESE Business School. Available at: https://www.onetoonefunds.com (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

Yale School of Management (2025). Exploring Post-Exit Dynamics for Search Fund Entrepreneurs. Yale SOM Research Paper. Available at: https://som.yale.edu (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (1988). Annual Letter to Shareholders. Berkshire Hathaway. Available at: https://www.berkshirehathaway.com (Accessed: 20 September 2025).

-

Cambridge Associates (2025). 2025 Outlook: Private Equity and Venture Capital. Cambridge Associates. Available at: https://www.cambridgeassociates.com (Accessed: 20 September 2025).